Did Behr Just [REDACTED] in the Woods?

- Mark Lipton

- 19 hours ago

- 3 min read

The economy of the United States was still recovering from the Great Depression in 1936, with unemployment down to 15% from its high of 25% in 1933. With Gross Domestic Product also on the rise, things were probably looking up for the first time since 1929 in my grandfather’s Bronx, New York, paint store.

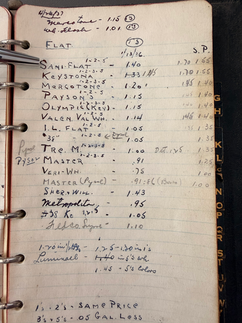

In an era before DIY projects and ready-made paints, customers in Gramps’ store were all painters, buying lead, solvent, pigments and driers in bulk before blending their own unique finishes on each job. More akin to artisans than laborers, painters of that era were known for their custom blends, leaving the painter as the brand and not the paint.

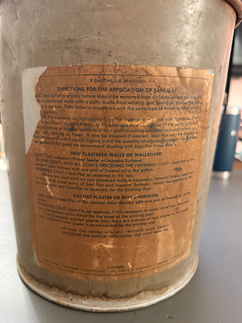

Any ready-made product Gramps did stock would have come only in white, with finishes limited to flat, gloss and enamel—a term of art used to describe every finish between those two before the marketing department came up with eggshell and satin. Among those products was Benjamin Moore’s Sani-Flat, an oil-based paint which was still a top seller when I came into the business some 50 years later.

By then it was my father’s store and Sani-Flat was an alkyd, though that reformulation didn’t cause any change of status for the top-selling brand. Alkyd Sani-Flat was available in a range of can sizes, though my father didn’t believe in such diversity. Insisting that fives were too heavy and that, “Any painter who needs a gallon of ASF will take two,” the deuce was Billy’s SKU of choice.

But more than just Billy’s preference the deuce was a New York icon, with most dealers in the city selling more volume in deuces than all other sizes combined when I joined their ranks in the late 1980s. An effect which remained until product rationalizations brought an end to local preferences.

Of the more than million deuces to pass through a Lipton’s hand, only one remains. Battered, rusted and misshapen from its journey, which based on my understanding of its history began on the third floor in Newark sometime during the 1930s.

When Ben Moore was paying a lot less for the empties.

In December I mentioned my plan to expand coverage to include all of the major paint brands, rather than just Benjamin Moore, Sherwin-Williams and Pittsburgh as has been my history. An undertaking made possible by the advent of artificial intelligence, with one prompt able collect more news and information in a moment than I could otherwise unearth in a month.

Included in that will be broader coverage of any lawsuits the paint manufacturers are a party to, as those claims often speak to a corporation’s practices and ethics.

In ABKCO Music & Records v Behr the paint maker stands accused of using the 1966 Rolling Stones hit “Paint it Black” in an advertisement with neither permission nor payment. The claim states that even after they were made aware of the breach Behr continued to use the song, which if true is not just incompetence but a staggering fatuity implying bad practice more than an inexperienced social media intern.

ABKCO’s initial claim does not specify damages, but don’t worry they’re getting to that.

Famously ruthless in pursuing copyright claims, ABKCO will not relent in their pursuit of Behr—which has probably spent more in legal fees than the license would have cost and they’re just getting started. Vexed, ABKCO claims that Behr is, “a sophisticated, multi-billion-dollar corporation who should have known better.”

Though having money doesn’t make you smart.

In a case filed in August Dunn-Edwards alleges that Vista Paint engaged in civil RICO against them, hiring Dunn employees and conspiring with them to steal proprietary information. Dunn claims 13 causes of action including breach of contract, unjust enrichment and theft including theft of documents which Vista conspired to receive.

And Dunn-Edwards brought receipts. Like Behr it seems Vista and poached Dunn-Edwards employees are about to learn a lesson in digital and intellectual property: access does create ownership.

In Reed v. Benjamin Moore & Co. a former employee accused the paint maker of failing to pay proper wages, including failing to pay for rest and meal periods missed between 2020 and 2024; which you know caught my attention.

Google’s Gemini AI summarized the case as more an aggrieved employee seeking requital than the beginning of a class action, suggesting that the plaintiff’s “venue shopping and soft particulars” make this more smoke than fire. That said, for a keystroke it still promised to follow the case through to adjudication, settlement or dismissal, which of course I’ll report here.

So Heidi knows I’m fair.